“Although the earth’s heat energy can’t be depleted by widespread geothermal energy production, individual geothermal reservoirs can lose heat energy over time, necessitating eventual re-drilling in a new formation, which adds to costs.”

Quick Bullets

- Geothermal plants produce 0.4 percent of the utility-scale electricity in the United States.[1]

- The United States also produces the most electricity from geothermal plants in the world.[2]

- Geothermal power is a renewable energy source that provides dispatchable, constant power, and is not dependent upon weather conditions.

- Expansion of geothermal energy use at the utility scale level is limited by the number of suitable locations.

Introduction

As mentioned in a previous report, “Energy at a Glance: Understanding Geothermal Power,” geothermal power has a range of applications. However, this paper primarily focuses on the economics of utility-scale geothermal power plants.

Growth and Cost

Geothermal is one of the least utilized energy sources in the United States. Despite this, the United States produces the most geothermal electricity in the world.[3] In 2021, about 16 million megawatthours of electricity was generated from geothermal sources. Megawatt-hours are a unit of energy use, or the electricity generated by a source over time. In this case, according to the average energy use of an American household,[4] 16 million megawatt-hours of electricity could power approximately 1.5 million homes per year.

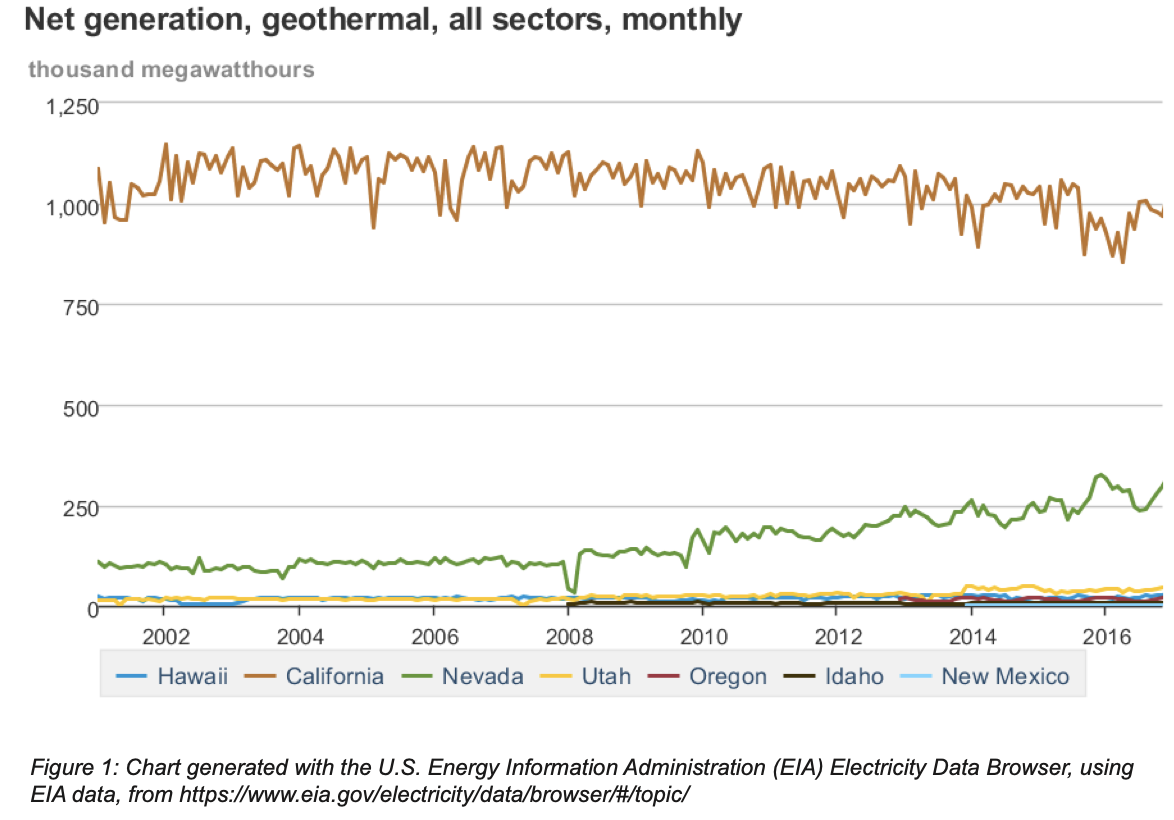

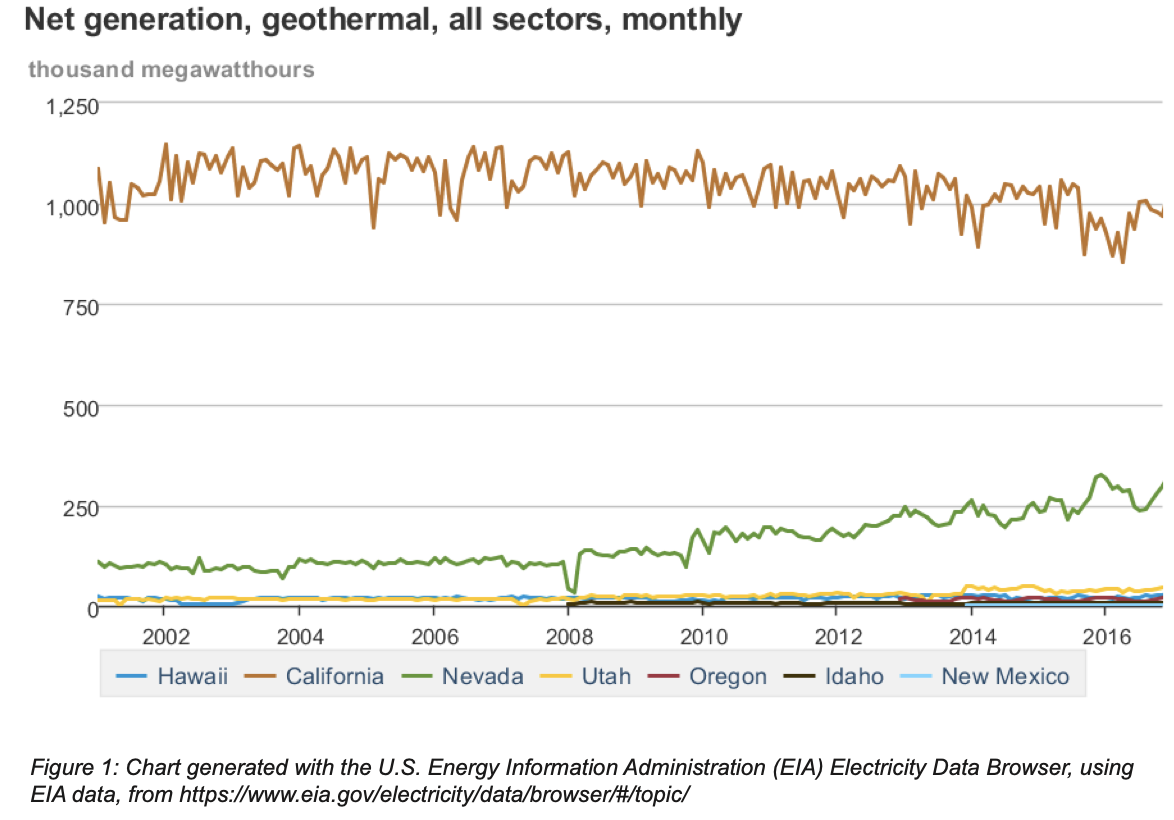

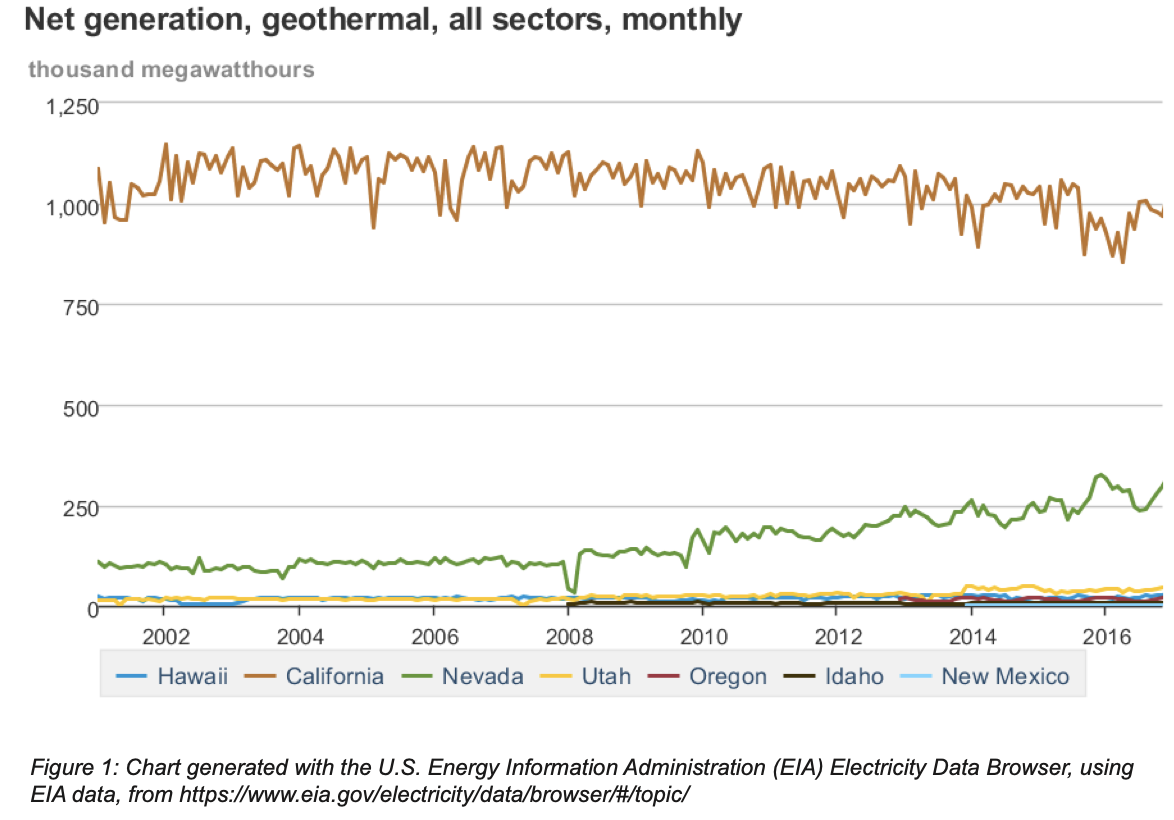

In the United States, California produces the most geothermal electricity by far, followed by Nevada, Utah, Oregon, Hawaii, Idaho, and New Mexico, as shown in the below graph based on U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) electricity data.

The county with the second-highest amount of geothermal power is Indonesia, which produces 5 percent of its electricity from geothermal, at 14 million megawatt-hours.[5] Iceland and New Zealand, both volcanically active islands, have success with geothermal utilities, with Iceland in particular getting about a quarter of its electricity from geothermal power.[6] Iceland has put geothermal to more direct use, with approximately 90 percent of homes in Iceland being heated by geothermal energy.[7]

Like other renewables, geothermal benefits from the Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit, at a rate of up to 2.6 cents/kWh.[8] Additionally, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Geothermal Technologies Office (GTO) receives tax dollars ($110 million in 2021) to fund research and development and other projects related to geothermal energy.[9]

Although the upfront development and construction costs of geothermal power plants are significant, their operating costs are relatively low, and they operate at a high capacity factor, producing 90 percent of their nameplate capacity.[10] EIA reports that the levelized cost of electricity for geothermal power is comparable to onshore wind or new natural gas plants.[11]

Two significant factors limiting the broader use of geothermal energy production are location siting and water types. The number of locations suitable for large-scale electricity production from geothermal resources are limited, with most of them located in the least populated areas of the country. This would necessitate the development of expensive infrastructure to deliver the power from where it is produced to where it is needed, which might be hundreds or thousands of miles away. Water type or quality is an issue because reservoirs with high concentrations of minerals and compounds can quickly clog up machinery and pipelines that come into contact with the geothermal fluids.[12] These combined factors limit the areas where it is feasible to develop utility scale geothermal power plants.

Although the earth’s heat energy can’t be depleted by widespread geothermal energy production, individual isolated geothermal reservoirs—or, those not immediately fed by a near-surface magma source—can lose heat energy over the span of several decades. This necessitates eventual re-drilling in a new reservoir, which adds to costs.[13]

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Explained,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/geothermal/use-of-geothermal-energy.php

[2] U.S. Department of Energy, “Electricity Generation,” Geothermal Technologies Office, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/electricity-generation

[3] Ibid.

[4] U.S. Department of Energy, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQS),” U.S. Energy Information Administration, Retrieved January 31, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=97&t=3

[5] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Explained.”

[6] Iceland National Energy Authority, “Geothermal,” Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://nea.is/geothermal/

[7] Iceland Renewable Energy Cluster, “Iceland Geothermal,” Retrieved January 25, 2023, from

https://energycluster.is/geothermal/#:~:text=Iceland’s%20first%20geothermal%20power%20plant,to%20electricity%20generation%20from%20geothermal

[8] United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit Information,” Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.epa.gov/lmop/renewable-electricity-production-tax-credit-information

[9] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Basics,” Geothermal Technologies Office, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/geothermal-basics

[10] Hans Engels, “How Much Does it Cost to Build a Geothermal Power Plant?” Costhack.com, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://costhack.com/cost-to-build-geothermal-power-plant/

[11] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2022,” March, 2022, Retrieved January 20, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/electricity_generation.pdf

[12] Ronny Boch et al., “Scale-fragment formation impairing geothermal energy production: Interacting H2S corrosion and CaCO3 crystal growth,” Geothermal Energy, Vol. 5, Issue 4, May 2017,

https://geothermal-energy-journal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40517-017-0062-3

[13] Drew L. Siler, “Why is geothermal energy a renewable resource? Can it be depleted?” American Geosciences Institute, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.americangeosciences.org/critical-issues/faq/why-geothermalenergy-renewable-resource-can-it-be-depleted

“Although the earth’s heat energy can’t be depleted by widespread geothermal energy production, individual geothermal reservoirs can lose heat energy over time, necessitating eventual re-drilling in a new formation, which adds to costs.”

Quick Bullets

- Geothermal plants produce 0.4 percent of the utility-scale electricity in the United States.[1]

- The United States also produces the most electricity from geothermal plants in the world.[2]

- Geothermal power is a renewable energy source that provides dispatchable, constant power, and is not dependent upon weather conditions.

- Expansion of geothermal energy use at the utility scale level is limited by the number of suitable locations.

Introduction

As mentioned in a previous report, “Energy at a Glance: Understanding Geothermal Power,” geothermal power has a range of applications. However, this paper primarily focuses on the economics of utility-scale geothermal power plants.

Growth and Cost

Geothermal is one of the least utilized energy sources in the United States. Despite this, the United States produces the most geothermal electricity in the world.[3] In 2021, about 16 million megawatthours of electricity was generated from geothermal sources. Megawatt-hours are a unit of energy use, or the electricity generated by a source over time. In this case, according to the average energy use of an American household,[4] 16 million megawatt-hours of electricity could power approximately 1.5 million homes per year.

In the United States, California produces the most geothermal electricity by far, followed by Nevada, Utah, Oregon, Hawaii, Idaho, and New Mexico, as shown in the below graph based on U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) electricity data.

The county with the second-highest amount of geothermal power is Indonesia, which produces 5 percent of its electricity from geothermal, at 14 million megawatt-hours.[5] Iceland and New Zealand, both volcanically active islands, have success with geothermal utilities, with Iceland in particular getting about a quarter of its electricity from geothermal power.[6] Iceland has put geothermal to more direct use, with approximately 90 percent of homes in Iceland being heated by geothermal energy.[7]

Like other renewables, geothermal benefits from the Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit, at a rate of up to 2.6 cents/kWh.[8] Additionally, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Geothermal Technologies Office (GTO) receives tax dollars ($110 million in 2021) to fund research and development and other projects related to geothermal energy.[9]

Although the upfront development and construction costs of geothermal power plants are significant, their operating costs are relatively low, and they operate at a high capacity factor, producing 90 percent of their nameplate capacity.[10] EIA reports that the levelized cost of electricity for geothermal power is comparable to onshore wind or new natural gas plants.[11]

Two significant factors limiting the broader use of geothermal energy production are location siting and water types. The number of locations suitable for large-scale electricity production from geothermal resources are limited, with most of them located in the least populated areas of the country. This would necessitate the development of expensive infrastructure to deliver the power from where it is produced to where it is needed, which might be hundreds or thousands of miles away. Water type or quality is an issue because reservoirs with high concentrations of minerals and compounds can quickly clog up machinery and pipelines that come into contact with the geothermal fluids.[12] These combined factors limit the areas where it is feasible to develop utility scale geothermal power plants.

Although the earth’s heat energy can’t be depleted by widespread geothermal energy production, individual isolated geothermal reservoirs—or, those not immediately fed by a near-surface magma source—can lose heat energy over the span of several decades. This necessitates eventual re-drilling in a new reservoir, which adds to costs.[13]

Endnotes

[1] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Explained,” U.S. Energy Information Administration, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/geothermal/use-of-geothermal-energy.php

[2] U.S. Department of Energy, “Electricity Generation,” Geothermal Technologies Office, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/electricity-generation

[3] Ibid.

[4] U.S. Department of Energy, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQS),” U.S. Energy Information Administration, Retrieved January 31, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=97&t=3

[5] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Explained.”

[6] Iceland National Energy Authority, “Geothermal,” Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://nea.is/geothermal/

[7] Iceland Renewable Energy Cluster, “Iceland Geothermal,” Retrieved January 25, 2023, from

https://energycluster.is/geothermal/#:~:text=Iceland’s%20first%20geothermal%20power%20plant,to%20electricity%20generation%20from%20geothermal

[8] United States Environmental Protection Agency, “Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit Information,” Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.epa.gov/lmop/renewable-electricity-production-tax-credit-information

[9] U.S. Department of Energy, “Geothermal Basics,” Geothermal Technologies Office, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from https://www.energy.gov/eere/geothermal/geothermal-basics

[10] Hans Engels, “How Much Does it Cost to Build a Geothermal Power Plant?” Costhack.com, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://costhack.com/cost-to-build-geothermal-power-plant/

[11] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Levelized Costs of New Generation Resources in the Annual Energy Outlook 2022,” March, 2022, Retrieved January 20, 2023, from

https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/pdf/electricity_generation.pdf

[12] Ronny Boch et al., “Scale-fragment formation impairing geothermal energy production: Interacting H2S corrosion and CaCO3 crystal growth,” Geothermal Energy, Vol. 5, Issue 4, May 2017,

https://geothermal-energy-journal.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40517-017-0062-3

[13] Drew L. Siler, “Why is geothermal energy a renewable resource? Can it be depleted?” American Geosciences Institute, Retrieved January 19, 2023, from

https://www.americangeosciences.org/critical-issues/faq/why-geothermalenergy-renewable-resource-can-it-be-depleted